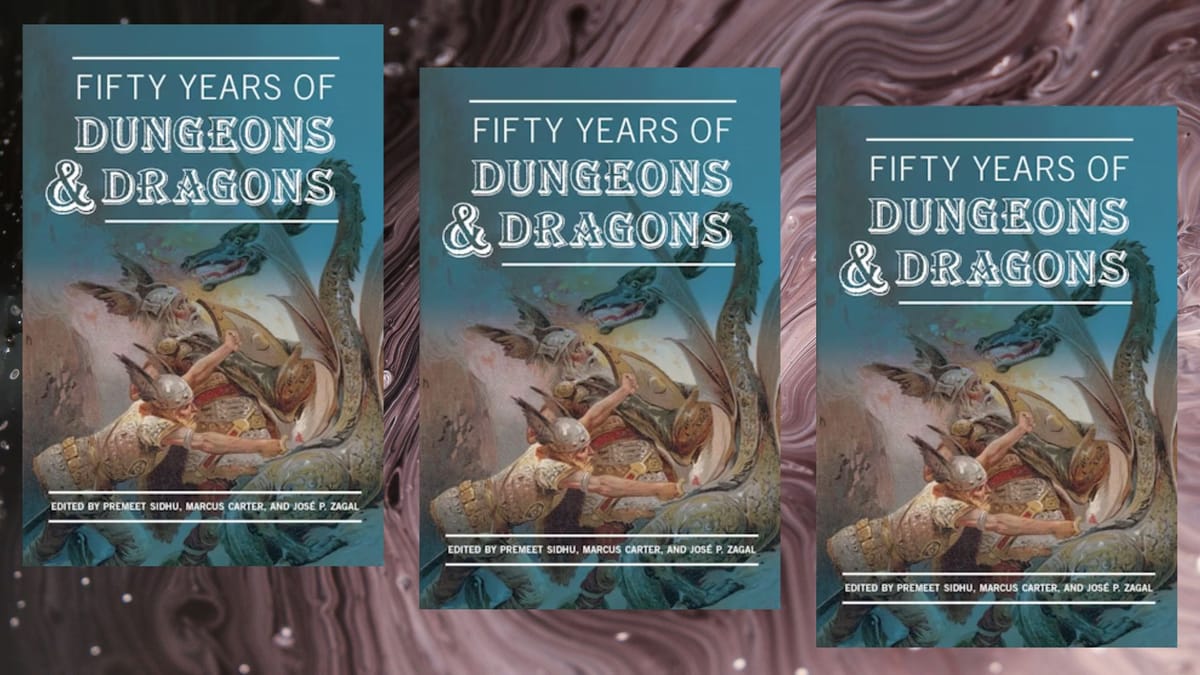

Combat in Dungeons & Dragons

A short history of design trajectories.

“Roll for initiative!” Across all editions of Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), that iconic phrase means two things. The first meaning is procedural: players roll a d20, add or subtract ability modifiers from the result, and declare the final number to the caller or dungeon master (DM), who determines which order the player characters (PCs) and their foes will act. The second meaning is liminal: PCs enter the “magic circle” of combat, in which special rules governing time, space, fictional bodies, player behavior, and abstraction itself now apply. No longer is the game paced mostly by the players’ conversation; now it proceeds at the rate at which player characters can mechanically overcome the combat obstacles—including the monsters’ very bodies—that stand before them.

Combat is central to D&D’s play experience. “A trip to the dungeon,” writes Jon Peterson, “continually flip-flops between exploration and combat until, as the rules prophesize, ‘the party leaves the dungeons or, are killed therein.’ ”1 Fighting often takes up the bulk of many game sessions. Yet both the game’s text itself and secondary literature about D&D focus more on players’ imagination,2 representation,3 and simulation.4 Character and world-building,5 or even ethical dilemmas posed by the game,6 dominate D&D discourse, despite the importance of (1) building and advancing a character that can survive and end combat encounters sooner rather than later, and (2) maintaining the necessary emotional, strategic, and attentional investment in those encounters when they come up. For example, I once played in a convention session using the 1977 D&D Basic Set and felt as if I had stepped into another world. There were eleven players, one of whom was our “caller,” who would collect all our actions and dice results to report to the DM. This hierarchy, I was assured, was a time-saving measure. The DM would record the actions and numbers in their notes and respond with statements such as “Claw, claw, bite, miss, hit Tyrin for 6 damage, miss.” The conversation was highly structured and regulated, with role-playing discouraged for efficiency’s sake. The lineage between tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs) and computer role-playing games (CRPGs) becomes painfully clear in these moments: the DM is best served by behaving like a computer program responding to player inputs; the computer in a CRPG becoming an algorithmic DM. PCs must then save characters in which they are emotionally invested from the churning grind of a battle.

D&D combat remains thus a mild embarrassment for D&D enthusiasts.

Gary Gygax, one of D&D’s creators, reportedly ran short combat rounds.7 If a caller was not present to “gather” all the players’ actions in a battle, Gygax would simply point at each player in initiative order to make their rolls. “Hit and a miss,” he would say. “Roll damage on the hit.” And then on to the next player. Scholars and players alike attribute great storytelling capacity to D&D,8 such that the ritualized, perfunctory speech acts of D&D combat rounds seem an odd counterpoint. Where is the sweeping narration of epic battles? Or the rhythmic and performative combat found in various human rituals over the past millennia? Instead, clarity and computation are sovereign in D&D combat. Again, to quote Peterson, “Dungeons & Dragons was the strategic campaign rules which linked battles run under Chainmail tactical miniatures rules.”9 In other words, rules and wargame culture from the early 1970s have more or less dictated the standard terms for all physical conflict in D&D-style TTRPGs for the past fifty years.

Role-playing itself is simply a structured conversation in which we manage our group’s consent to fictional events. This point was raised by Emily Care Boss, as well as Vincent and Meguey Baker, in the “Baker–Boss Principle”:

The fictional events of play in a role playing game are dependent on the consensus of the players involved in order to be accepted as having occurred. All formal and informal rules, procedures, discussion, interactions and activities which form this consensus comprise the full system used in play.10

Combat in D&D constitutes a special form of conversation: highly structured, ritualized, and purposefully devoid of the chaos of real fighting. Yet it is also a moving, intense narrative experience; an emotional roller coaster of decisions, rolls, and outcomes. D&D combat quantifies the bodily integrity of all its participants through “hit points,” with the roleplaying conversation unable to proceed beyond combat itself until the enemies’ hit points are reduced to zero.

None of the assumptions underlying this special form of conversation are inevitable: they emerge from deliberate design and established tradition. Moreover, they have shifted over the past fifty years. Whereas early editions of the game were caught in a genuine tension between realism and playability,11 later ones have marked a design struggle between playability, supplement bloat, and player agency. A rich history of D&D combat encounters has meant that hundreds of designers grapple with basic dilemmas: Are the enemies numerically too difficult? Does the encounter last too long? Can one model this encounter with maps and miniatures, or are we using theater of the mind? Do the player characters have reasonably interesting choices, both in the situation and in the system itself? This chapter explores how D&D combat has developed over time, and what D&D combat means. To accomplish this, I first describe its core mechanisms and what D&D combat encounters of today inherited from Chainmail, D&D’s predecessor system. Then I will traverse the winding terrain of D&D’s different editions and their various treatments of the combat encounter—always as an ongoing design problem—to demonstrate how shifting conceptions of the D&D player dictate how combat is to be resolved. Finally, I discuss some core values and assumptions of D&D combat and its meaning, in my interpretation. D&D combat intends to provide a thrilling narrative experience for the players, but ironically its design tradition means dropping a not necessarily consensual conversation into a shared role-playing game (RPG) narrative. Players are intended to be free to choose among many options, while often being deprived of the greatest option of all: to refuse to fight.

Different editions, different wars

D&D has had more than ten editions since 1974. Describing D&D’s combat shifts over time tells us what values did change, despite its Chainmail core. Chainmail had no DM; all editions of D&D have required at least one. Chainmail required miniatures; D&D transferred notions of combat space to the imagination and theater of the mind. Chainmail was about squad combat and attainment of battle victory conditions; D&D turned to individuals and their acquisition of treasure, experience, and magical equipment as they traversed, puzzle solved, and battled their way through various dungeons, castles, caves, ruins, and even wilderness sites. Mechanically speaking, combat in Chainmail relied on players rolling six-sided dice, consulting tables, and tabulating effects of troop deaths on squad units (including morale). D&D kept the tables but introduced (thanks to the Bristol Wargames Society and Lou Zocchi) various polyhedral dice to roll to hit (the d20) and to roll separately for damage (the d4, d6, d8, d10, and d12). Damage in D&D was calculated not in troop losses but in the personal bodily abstraction of “hit points.”

The innovations of hit points, experience points, and differentiated to-hit/damage dice rolls alone let D&D completely and irrevocably change the design of fantasy wargaming and TTRPGs. D&D stressed the individual combatant’s bodily integrity, damage-dealing potential, and overall improvement over time. Morale, which focuses on the collective over the individual, would still be in play but was overtly downplayed in favor of the ever-stimulating nature of life-and-death struggle. We must keep this tension between tactical simulation and individual heroics (and death) in mind as we examine fifty years of combat procedures.

Rules and wargame culture from the early 1970s have more or less dictated the standard terms for all physical conflict in D&D-style TTRPGs for the past fifty years.

Because original D&D (OD&D) is preoccupied with the simulation of medieval violence, a discomforting level of complexity is introduced around armor and armor class. The baseline of the game is to roll a die and then consult the right table. In AD&D, a low armor class (even in the negative numbers!) was good, making one harder to hit. In AD&D 2e (as well as in the OD&D Dungeon Masters Guide), early armor to-hit tables were substituted out with the “To Hit Armor Class 0” (THAC0) stat on a PC’s sheet, which saved time but confused beginners. Issue 74 of The Dragon magazine even introduced a spinning-wheel “combat computer,” permitting quicker tabulation of all the variables in a single attack at a game session. Wargaming’s reliance on tables for modeling conflict lies at the center of this design. Individual heroics were not prioritized in this simulation at first but would become more pronounced as TSR produced ever-widening sets of rules.

AD&D 2e combat unintentionally metastasized. Supplement after supplement, including books such as The Complete Fighter’s Handbook (1989) and the Arms and Equipment Guide (1991), expanded the player’s options in preparing for fights. This included taking prestige classes such as the “cavalier” that afforded extra attacks, and introduced all the optional rules that made combat last even longer: called hit-location shots, held attacks, fighting styles, unique weapon rules, and more. Although these supplements made revenue for TSR, D&D’s publisher at the time, DMs had difficulties in accounting for all the variables and player options in a given fight, rendering late-1990s AD&D combat largely unplayable with the introduction of even one or two optional rules from supplements.

Tasked to overhaul D&D for its new owners at Wizards of the Coast and Hasbro, Monte Cook and Jonathan Tweet created D&D 3e (subsequently revised as 3.5e and then as Pathfinder) to simplify and declutter the whole system. Here, saving throws transform from the specific threat titles such as “Breath Weapon” to “checks” made against a PC’s stats and a difficulty class number. Cook and Tweet also made armor class something one would want more of, translating complicated armor and to-hit tables into an easy-to-use set of stacking bonuses added to a d20 roll against a reasonably determined value. “Feats” were added to give characters special abilities. D&D 3e and 3.5e bear the influence of Eurogame-style elegant design: that the terminology and choices in the game should be immediately intelligible to all who might play it. Players understanding the game itself got more agency over their PCs’ fate.

D&D 4e (2008) sought balance over that particular form of agency. Made in the shadow of World of Warcraft (2004–) and other competing fantasy products, D&D 4e was a purely combat-based miniatures game that afforded each character comparable advantages on the battlefield. This meant a standardization of various components of character building. Classes are described purely by their combat function—controller, defender, leader, or striker—and each gets a reasonable assortment of combat “powers,” which are based on how often one can use them: at will, per encounter, or daily. Fourth edition improved D&D as a tactical combat game by providing PCs clear options in every fight, and a range of options beyond standard sword swinging for ten to fifteen rounds.

But D&D 4e wasn’t successful despite its emphasis on game balance. D&D 5e showed the video game cultural shift from World of Warcraft to Dark Souls (2011). Dark Souls is unconcerned with encounter balance, preferring player dexterity and ingenuity for difficult enemy encounters. Player intelligence, coupled with fictional positioning, would intervene to rebalance the game in the players’ favor. Consequently, combat balance was discarded: the dice will not go in your favor, so try to use your own wits as a player to seek ways of not rolling them. Combat in D&D 5e returned to an endless procession of rounds, which take up the majority of a session.

Core assumptions and values of D&D combat

On February 19, 2022, Misha Panarin wrote on Twitter, while subtweeting the head D&D designer Ray Winninger:

The weirdest thing about [D&D] fans (and, apparently, head designers) is that the self-evident truth that D&D is a game whose core gameplay loop and reward structure is combat puts them on the defensive instead of going “yeah and I like it that way” or “yeah but whatever.”26

Panarin highlights a noticeable anxiety within D&D fandom about how much combat dominates both the D&D books and the game itself. For context, Winninger had repeated a standard line of accepted D&D discourse that although the combat system is paramount to the D&D experience, he doesn’t use it very much. Such a contradiction between inscribed rules intention and actual player usage could be chalked up to brand marketing—D&D sells better as a vehicle for exploration and storytelling than as a repackaged wargame and dice roll-off—but is nevertheless interesting to pursue.

In AD&D 1e (1977), Gygax writes: “Combat occurs when communication and negotiation are undesired or unsuccessful. The clever character does not attack first and ask questions (of self or monster) later, but every adventure will be likely to have combat for him or her at some point.”27 Yet combat in D&D is inevitable. As Panarin pointed out, one could simply acknowledge enjoyment of this game rhythm. D&D 4e indeed tried to address this issue by at least balancing different characters’ effectiveness in combat so that all PCs could contribute strategically to a fight. However, such balance was not necessarily desired by D&D’s player base. For example, the Australian TTRPG critic Merric Blackman comments on the pacing and difficulty of D&D combat:

When people want “balanced” combat in Dungeons & Dragons, they don’t want combat that is a 50/50 chance of either side winning. They want combat that the PCs will almost always win, but *feels* like they might lose. As you might expect, this is a bit tricky to pull off!28

Thus one chimera of fifty years of D&D combat history comes into focus: whether player agency and true randomness are important, or rather player emotion and weighted randomness. Give players a “fair” fight, and they may perceive that the deck is stacked against them anyway. Make a fight too easy, and the players lose interest in the overall challenge of fighting. Make the fight too hard, and the players can neither advance the plotline nor enjoy themselves in a straightforward fashion. D&D both shackles the “anything can be attempted” freedom of a TTRPG or refereed wargame to a dense set of variables (e.g., PC abilities, monster stat blocks, and the rules themselves) and then asks the DM to not-so-obviously weight a difficult encounter in the PCs’ favor. DMs can “fudge,” or directly alter, dice roll outcomes to let the gameplay meet player expectations when the system fails to perform.

Ideology and Combat

D&D combat remains thus a mild embarrassment for D&D enthusiasts, as well as a long-term problem seeking endless correction in its design. Thoughtful players admit this and frequently accept the uneven foundations of D&D combat so that they might still participate in a rich play culture and shared fantasy imaginary. But as Mary Flanagan and Helen Nissenbaum remind us, even in complex games, one can “[locate] the values that are relevant to a given project and [define] those values within the context of the game.”29 These combat systems are not value neutral and deserve further examination.

Modern wargaming itself emerged in reaction to World War I, “not only [providing] a harmless setting in which human beings could face some of war’s challenges without destroying lives, property, or nature, but also taught something of the reality of [the] Great War to those not familiar with its practice.”30 However, this granted a kind of sacred ritual space to combat. Combat takes up its own “special” time in the gameplay31 and has its own logic for space, bodies, potentialities, and basic math. Nineteenth-century wargame traditions let Prussian officers attempt anything to win a wargame scenario, whereas in the mid-twentieth century, the Cold War brought about the quantification of everything, a world mapped in “targets and numbers.”32 D&D’s unique combat system emerged from these two trends. As I have previously written, “a combat system usually arbitrates three major dimensions of a diegesis: time, space and the body, often described in that order within TRPG combat rules. Separate rules arbitrating these dimensions delineate combat from other contests, conflicts, and methods of resolution.”33

With the discarding of morale, hit points become the primary counter for D&D combat time. A player should want to minimize their time in combat, for it will then reduce the possibility of something in the fight killing their PC. This means the best choices for a player during character creation and beyond would be those that let them hit in combat as often as possible for as much damage as possible. Certain forms of min-maxing behavior can be linked not to player dysfunction but to a genuine urge to maximize one’s effectiveness against potential elongation and complication of future combat. One must transform one’s character into a killing machine, often because one is otherwise at the mercy of the DM and the D&D combat round structure. Even the tiny “optional” morale section in the D&D 5e Dungeon Master’s Guide remarks that a “failed saving throw isn’t always to the adventurers’ benefit. For example, an ogre that flees from combat might put the rest of the dungeon on alert or run off with treasure.”34 Killing the ogre, as the text implies, will actually ensure a smoother time for the adventurers.

This brings us to the narratives of warfare that D&D combat tells. When a monster is reduced to zero hit points, it is removed from the fight; it is ambiguously “dead.” “Looting” the body is often a standard practice.35 Here the annihilation of “humanoid” monsters in D&D combat is cleansed through rules and abstractions. Grant Piper writes of how “extremely brutal” medieval warfare actually was, and how “many people take the heroics from these times without taking the necessary reality that these battles produced.”36 D&D combat lets modern abstractions dominate both the realm of myth and legend and the realm of medieval warfare, cleansed of smell and moral turpitude. It is simply difficult to imagine medieval genocidal warfare, so one chooses to “master” it through the D&D combat metaphor. In its design, D&D combat translates the fantastical into the mechanical and tactical. This moment of numerical diminution, of giving even gods “armor class” and “hit points,” shows how D&D renders all beings intelligible: as potential participants in a fight. Without many alternatives to fighting, D&D in general does not give PCs good tools to de-escalate a conflict, or to suffer an enemy to live. The stories D&D tells would be much different if the lives of NPCs and monsters had any value, if they weren’t just bodies of hit points standing between the players and the next chapter of the story.

NOTES

(all included)

- Jon Peterson, Playing at the World (San Diego: Unreason Press, 2021), 321.

- Nicholas J. Mizer, Tabletop Role-Playing Games and the Experience of Imagined Worlds (Palgrave, 2019).

- Aaron Trammell, “Representation and Discrimination in Role-Playing Games,” in Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations, ed. José P. Zagal and Sebastian Deterding (Routledge, 2018), 440–447.

- Peterson, Playing at the World.

- Kat Schrier, Evan Torner, and Jessica Hammer, “Worldbuilding in Role-Playing Games,” in Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations, ed. José P. Zagal and Sebastian Deterding (Routledge, 2018), 349–363.

- Christopher Robichaud and William Irwin, Dungeons & Dragons and Philosophy: Read and Gain Advantage on All Wisdom Checks (Wiley-Blackwell, 2014).

- Ernest Gary Gygax, “Letters,” White Dwarf, no. 7 (1978).

- See Stephen Cloete, Gaming between Places and Identities: An Investigation of Table-Top Role-Playing Games as Liminoid Phenomena (MA thesis, University of Witwatersrand, 2010); Jennifer Ann Grouling, The Creation of Narrative in Tabletop Role-Playing Games (McFarland, 2010).

- Peterson, Playing at the World, 321n199.

- Emily Care Boss, “Lumpley Principle (or Baker–Care Principle or Baker–Boss),” Black and Green Games, 2021.

- Peterson, Playing at the World.

- Bernard Suits, The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia (Broadview Press, 1978), 54–55.

- Peterson, Playing at the World.

- Steven Dashiell, “Rules Lawyering as Symbolic and Linguistic Capital,” Analog Game Studies 4, no. 5 (2017).

- Gary Gygax, Players Handbook (AD&D 1e) (Lake Geneva, WI: TSR/Random House, 1978), 104.

- Nicholas St. Jacques and Samuel Tobin, “Death Rules: A Survey and Analysis of PC Death in Tabletop Role-Playing Games,” Journal of Japanese Analog Role-Playing Game Studies 1 (2020): 20–27.

- Peterson, Playing at the World, 321.

- Erick Wujcik, “Dice and Diceless: One Designer’s Radical Opinion,” The Forge, 2003.

- Chris Chinn, “Fictional Positioning 101,” Deeper in the Game, March 8, 2008.

- For further information, see Peterson’s chapter in this collection (chap. 3) and his book Playing at the World (2012).

- D. H. Boggs, “Blackmoor as a CHAINMAIL Campaign,” Hidden in Shadows (blog), July 20, 2017.

- Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren, Chainmail 2e (Evansville, IN: Guidon Games, 1971), 7.

- Gygax and Perren, Chainmail 2e, 11.

- Gygax and Perren, 15.

- Gygax and Perren, 18.

- Misha Panarin, “The weirdest thing . . . ,” Twitter, February 19, 2022.

- Gary Gygax, Players Handbook (AD&D 1e) (Lake Geneva, WI: TSR Games, 1978), 104.

- Merric Blackman, “When people want . . .” Twitter, November 19, 2021.

- Mary Flanagan and Helen Nissenbaum, Values at Play in Digital Games (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014), 75.

- Peter Perla, Peter Perla’s The Art of Wargaming (Bristol, UK: History of Wargaming Project, 2011), 169.

- Evan Torner, “Bodies and Time in Tabletop Role-Playing Game Combat Systems,” In WyrdCon Companion Book 2015, ed. Sarah Lynne Bowman (Los Angeles: WyrdCon, 2015), 160–176.

- Adam Curtis, dir., The Trap (BBC, 2007).

- Torner, “Bodies and Time,” 164.

- Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, et al., Dungeon Master’s Guide (D&D 5e) (Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast, 2014), 273.

- Esther MacCallum-Stewart, Jaakko Stenros, and Staffan Björk, “The Impact of Role-Playing Games on Culture,” in Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations, ed. José P. Zagal and Sebastian Deterding (New York: Routledge), 174.

- Grant Piper, “The Inhumanity of Ancient and Medieval Warfare Cannot Be Understated,” Medium, September 14, 2021.

- Perla, Art of Wargaming, 264.