Orbital Blues is a game so good it doesn’t need its rules

This game makes me so fucking sad, I don’t ever want to play a game that doesn’t make me this sad.

Captain Vasko doesn’t look like a captain. She’s a short, rangy fifty-something with a smoker’s rasp and lots of small scars along her hands and arms. What she lacks in authority she makes up for in space smarts, pure grit, and a knack for self-preservation that younger dead lack. She spent nearly fifteen years in a small cell, dreaming of space, and now that she has the universe to travel, she sticks to the lanes she knows. As much as possible, at any rate. When she travels above the disk, when she sees the starless expanse of this galaxy, she realizes how comforting it is to rely on walls, and lights up her half-ashed joint.

She’s got two folks on her crew. The first is Taka Haye, a former medical wunderkind turned incorrigible gambler. He’s a fallen socialite and an absolute asshole who Vasko keeps around because he has never failed to patch up a man after a shootout. He resents the life he lost, drowns his regrets in whiskey and men. Vasko feels bad for him. He used to live on Earth. The real Earth. She doesn’t ask questions about what green looks like.

Billie came from a damp mushroom farming planet—an AgraStar subsidiary where every birth is logged in the employee record kept by corpodoctors and company script is the only kind of credit on the entire globe. Tall and imposing, her naivete and sweetness makes Vasko wish that Billie had chosen a better ship to hitch her ride to. She’s got fungi growing in the corners of the ship and makes shroomshine to give away to new friends. At least now she’s got a union card.

This is the crew of the Dead Moon—a former cruiseliner that Vasko found half-abandoned in a wrecker flat. She bought the beast for a song and spent a few years gutting it and getting all the right permits to make it a trucking ship. She’s above board now. Signed up with the Shipping Guild and more than happy to travel back and forth across the galaxy. She makes just enough creds to keep her weed stash stocked and the Dead Moon comfortably outfitted.

This is the cast of the Orbital Blues game I play with four of my friends. We aim for every other week, but our last session was our first since October. I play Vasko. She’s a chain smoking, easy-going bleeding heart despite her own assertions she’s a hardass motherfucker. Jensen, a soft-spoken, big-shouldered tattooed firefighter with a Warhammer problem, plays Taka—a man who is his polar opposite in almost every way. Beth, one of my best friends, a delightfully nerdy librarian who regrets attempting to romance Shadowheart in Baldur’s Gate 3 (“She’s a prude!”) plays Billie—they’re more similar than you’d think. Leland, another one of my best friends, (and Beth’s husband) is our GM, and despite his incredibly laid-back personality, he can summon take-no-shit PC voices and personalities without blinking an eye. It’s scary. Impressive. And very scary.

Despite not having played in a while, we jump right in. We’re landing the Dead Moon—currently assigned a new name, the Sandra Anne—on Davrok. This is a detour; our goal is to get Park Sun-sik, a union director, to Tamaru without anyone realizing. (Tamaru is currently experiencing some kind of worker’s boom; the union wants to get there before a corporation can exploit the shipping crews.) We’re stopping on this abandoned corpoplanet owned by a holding company that shuttered before they finished terraforming to pick up some organizational literature. This will go to Luzon Station, just above Tamaru.

But as the Sandra Anne descends into the Kulfira-branded spaceport there’s nobody checking our credentials. There are two men with machine guns guarding the landing strip, but nobody else. There aren’t even any other ships here. It’s a desolation and a threat at the same time.

The three security men that Director Park brought with her are not going to pick up the pamphlets. For some reason, fetching the paper falls to Vasko and her crew. Billie is thrilled: she’s demanded to drive whatever vehicle Park has secured for us. Taka volunteers to stay on the Dead Moon, with the left-behind security guards, his carnal intentions evident. Vasko doesn’t have it in her to argue. She gets a terrible, unrelenting shiver in the back of her neck, where a long scar marks a point in between the Atlas and Axis vertebrae, the surgical incision where her prison tracker was put in, and later, roughly removed.

First Canto:

Dead Moon Night, Dead Moon

Midnite Blues, The Detroit Cobras

There But for the Grace of God Go I, The Gories

Black Sheep, Metric/Brie Larson

Walk Like a Motherfucker, Ghost Funk Orchestra

Outsider, Ben Miller Band.

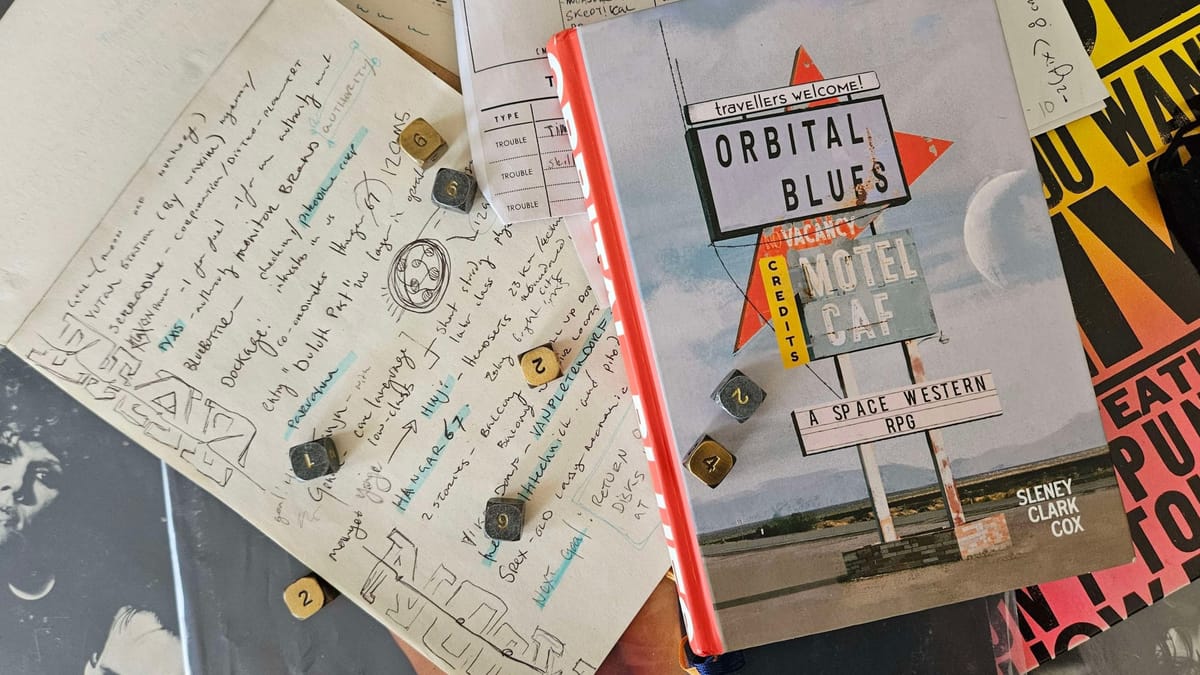

Orbital Blues is a game about sad space cowboys trapped in a gig economy against a backdrop of galactic corporations. There is no escaping the grind, there are only dreams of freedom on the empty frontier of nothingness. It is built in an anachronistic rock-and-roll retrofuture, and every player character is some kind of interstellar outlaw. Mental health and examining how characters cope with a futility that threatens to drown them is front and center in the book. Music, soundtracks, and records carry a lot of weight in the flavor of the game, and players are encouraged to make playlists for their characters. Vasko’s playlist is included in this piece.

Produced by Soul Muppet Publishing, Orbital Blues was written by Sam Sleney and Zachary Cox. Josh Clark also gets topline credit for his art and maps, which transform the Orbital Blues book into a heritage piece, each page full of vintage castoffs and illustrations. Lone Archivist did the layout and helped with the maps as well. It uses a modified Best Left Buried system that asks for stat checks with 2D6. There's even a new expansion: Afterburn.

The core mechanic of Orbital Blues the Blues Check. When your character gets sad, typically because of something that reminds them of their past, you roll to see if you let that feeling overwhelm you or if you shake it off. If you succeed on a Blues Check you get overwhelmed, but you also get a Blues. Blues are experience points you can spend to take control of a situation and level up your character. The driving force of the game is to put your character in situations where they feel as deeply as possible as often as possible.

My group is heavy on the roleplay, light on rules. Leland is a fantastic GM, and he’s been known to spend hours developing intricate factions for us to bump up against. We’ve encountered the future evangelicals, found the space Nazis, rescued indentured miners from a decaying space station, scrounged a Cloud relic out of a dusty pawn shop, and neatly avoided a fight on a poisonous planet by simply kicking a shipment out of the bay while the Dead Moon hovered a few feet from the ground. If there’s a fight on the horizon, Vasko takes a hard left, and neither Taka nor Billie are eager for combat. We want to do the job and we want to enjoy our union-mandated shore leave. We’re not heroes. We don’t want to be.

Orbital Blues is not a game built for heroics. It’s a game built for resource management and survival. It’s a game that encourages connections by giving players no other choice—either we learn to live with our pasts or the future will destroy us.

The crew of the Dead Moon doesn’t shoot first. We’ve got revolvers and mushroom-harvesting knives. Think about what we’re up against. We’re outnumbered in every situation. We keep our heads down, trading favors and whispers under neon lights, bartering for information and trying to keep one step ahead of Centuricon Defense Systems. We’ve got people after us, and we’re fucking nobodies. Imagine how much worse it would be if we tried to be heroes.