Titan Takedown taught me to love professional wrestling

Dimension 20's latest actual play takes wrestling from the oligarchs and gives it back to the people.

Titan Takedown, the most recent season of Dimension 20, brought together an inevitable pairing — professional wrestling and actual play.

“There is an obvious dotted line between people at the apex of performance arts that lend themselves to larger-than-life performance,” said Game Master Brennan Lee Mulligan in a press roundtable with Rascal. Much like Dimension 20's previous crossover season Dungeons & Drag Queens featured well-known drag queens, this limited-run season featured real life wrestlers at the peak of their craft. Titan Takedown transports hyper-stylized characters from the ring to the table, trading costumes and choreographed routines for a character sheet and a set of dice.

“On first blush it can be somewhat silly to imagine that there is overlap between the worlds of tabletop roleplaying games and wrestling,” said actual play performer Dare Hickman in a message to Rascal. “But that fails to recognize the overlap between both mediums. Both contain larger-than-life characters, many of whom are an exaggeration of aspects of the performer. A [wrestling] botch (a genuine mistake) is similar to how one unexpected roll can completely alter the course of a character. Poor audience reception can change or derail an entire narrative, creating some truly magical moments of emergent storytelling.”

The latest Dimension 20 season leans into these similarities. “D&D, professional wrestling, and Greek mythology all have this [shared presentation],” said Mulligan. “You can call it tall tale. You can call it epic myth. You can also call it camp. The sequined-covered spotlights, lasers, the gods, Olympus, the big kind of storytelling.” Titan Takedown follows four WWE Superstars; Xavier Woods, Bayley, Kofi Kingston, and Chelsea Green, playing as underdog monsters from Greek mythology. Each one is cursed, and all four enter into a wrestling tournament to claim a seat on the pantheon. The tournament is run by Zeus, called “Big Z” throughout the series, who Mulligan portrays as a mixture of Vince McMahon and Macho Man Randy Savage. The season is flashy, utilizing the developed technology, prop work, and miniature battle sets to bring the spectacle of professional wrestling into the iconic D20 dome.

As a journalist and actual play critic, it felt like my responsibility to cover this historic synthesis of these two pop culture phenomena. But I have a confession to make: I’ve never liked wrestling.

I know, a strong way to start off a piece about the art form — but stay with me. I’ve never liked wrestling, because it never seemed like wrestling wanted people like me. I was introduced to it young, at seven or eight, when a family friend’s son opened up a set of WWE action figures for Christmas. It was anathema to me, a closeted young (at the time) boy. Why was it okay for my friend to play with plastic figures of nearly naked men climbing all over each other, when bringing a High School Musical lunch box to school got me called a faggot by him and his friends? Wrestling became a symbol of the type of boy I didn’t want to be — one I couldn’t be if I tried.

Years later, I made the delicious discovery that wrestling wasn’t real. They were all playing pretend, no different from my friends in the theater. I felt a moral superiority I could lord over fans of the form. At least I was honest with myself, that my passion for make believe didn’t have to be hidden behind a veneer of reality.

"I have a confession to make: I’ve never liked wrestling."

I only felt more justified in my derision as time went on, as I learned that the people who operated the WWE were cruel and abusive. WWE Founder Vince McMahon’s cultural and literal monopoly on the artform allowed him to burn out talented performers like cigarettes, tossing them aside as their bodies crumpled to ash. McMahon stepped down as CEO of WWE in 2022 after a federal investigation into hush money payments — only to be replaced by his daughter and subsequently return as executive chairman in 2023, before stepping down again in 2024 after being faced with allegations of sex trafficking. Those allegations became the subject of an investigation under the Biden administration. Under the new regime, it would be safe to assume those charges will be dismissed entirely. However, that exploitation isn't contained within the confines of his company.

Outside of wrestling, Vince McMahon’s co-founder and wife Linda McMahon used her entertainment-based connection with WWE guest star Donald Trump to land a seat in the presidential cabinet, first as administrator of the Small Business Association in 2017 and as the current Secretary of Education — an ironic title as she works to actively dismantle the United States’ public education system. The gods in Dimension 20’s Titan Takedown represent these types of people: narcissistic, power-hungry egomaniacs who crave worship, but rule with fear.

Even still, people I respect and care about love wrestling. People whose politics stand in opposition to everything McMahon represents adore the spectacle of it. “The people I know that are fans of professional wrestling are some of the farthest left, most anarchist [people],” said Mulligan, sharing my experience. “They love it with all their hearts, even knowing that there are people associated with it doing things that politically we absolutely object to and disagree with.”

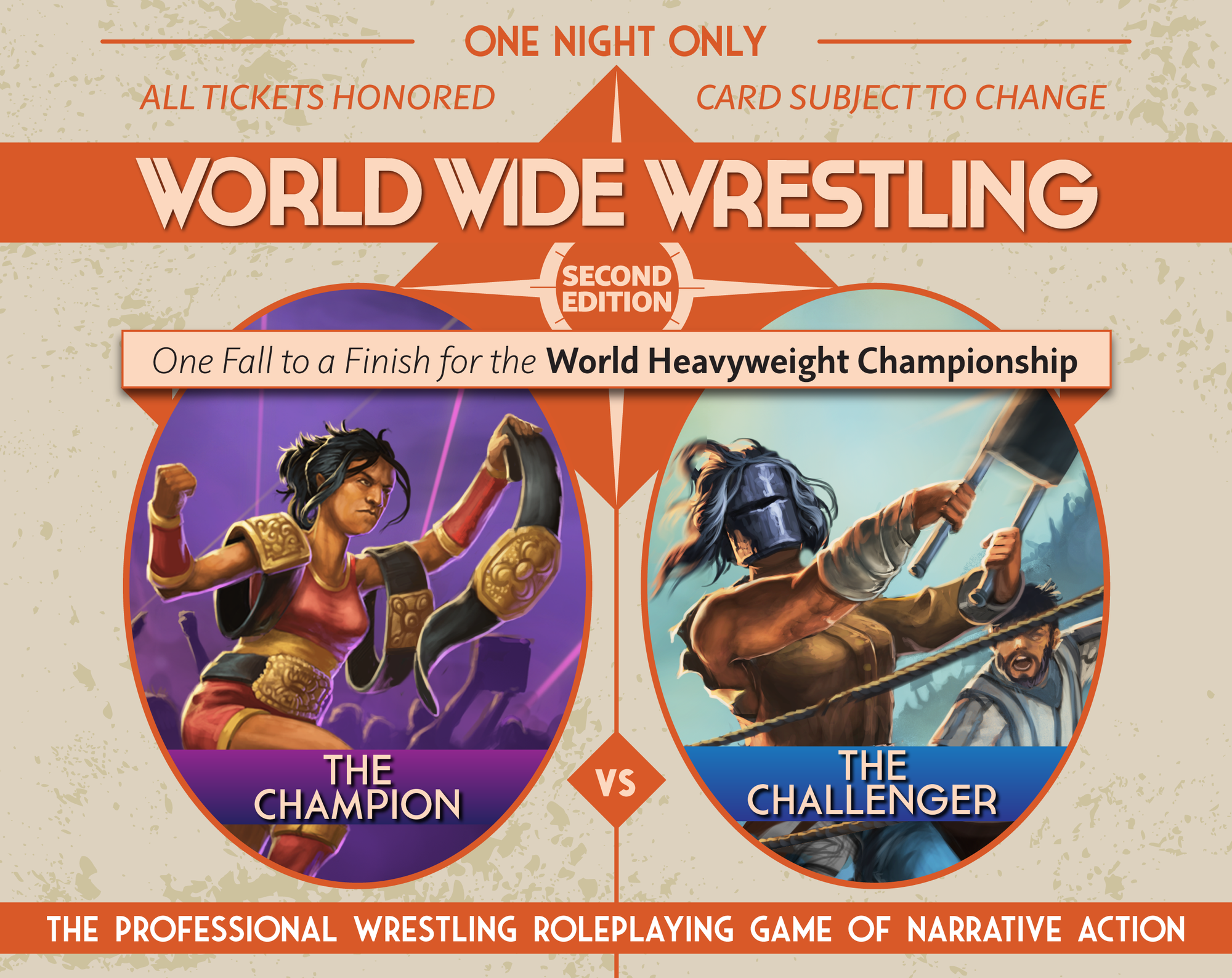

I didn’t understand it, but I was determined to figure it out, to see the appeal. It all began to align when I cracked open the 2nd Edition of World Wide Wrestling by Nathan D. Paoletta. Game designer and Party of One host Jeff Stormer’s essay “We’re All Players In The World’s Greatest LARP,” revealed the artistic depths of wrestling that I'd never considered. To open the piece, Stormer uses a hypothetical: if during a production of Hamlet, an audience member threw a cup of soda and began voraciously booing the play’s antagonist, it would be a breach of etiquette. When the same is done at Wrestlemania, it’s an inherent part of the experience. The audience of a wrestling match is not just the audience. They are playing a character themselves, Stormer explains, “choosing to, for the duration of the show, inhabit a world where the action on-screen is ‘real’... and you are being asked to act in a way that reflects that belief. Pro wrestling is an artform that asks you to roleplay.”