What we miss when play is only pleasurable

Professor Aaron Trammell on torture, military strategists at conventions, and learning from his cats.

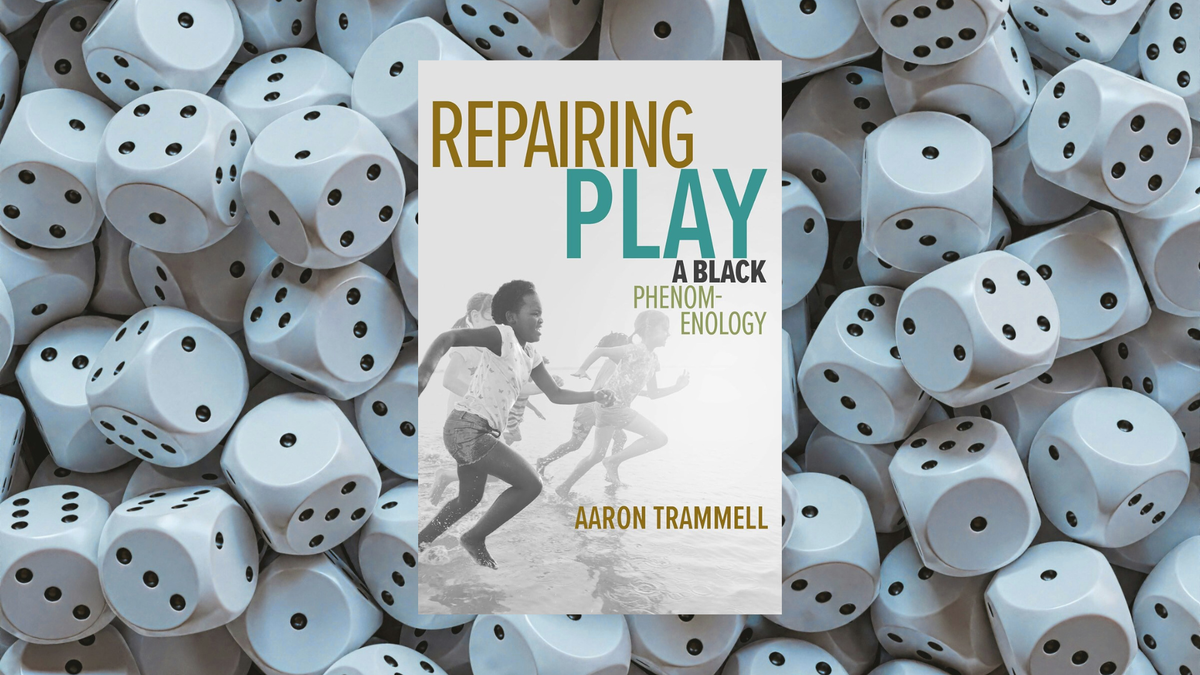

Last week, before history week was history, we published an interview with Analog Games Studies’ current editor-in-chief, Edmond Chang. They mentioned taking over for previous EIC Aaron Trammell and even mentioned his 2023 book, Repairing Play: A Black Phenomenology, when discussing heartbreak at the table and how fun can come at the expense of others. As it so happened, Rowan had an interview with Trammell waiting in the wings.

Trammell, a professor of informatics at UC Irvine, told Rascal that we might simply title him as a professor of games (“We still have no idea what informatics is, but we know what games are”). The son of one of the first Black men in the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, he broke from the film industry to seek a career in academia, first as a grad student at SUNY Binghamton and then later at Rutgers University’s media studies programming. At every step, he chased an old urge born from reading pop culture game studies articles online while working a temp job at a Verizon Wireless outlet.

The journey brought Trammell into contact with post-structuralism, sound studies, cultural studies, and — finally — games. Once there, he began toying with ideas around play’s uncomfortable dichotomy, and how pop culture overwhelmingly champions a sanitized relationship between play and fun. Inherently rooted in a white, predominantly Eurocentric understanding, this version of play avoids coercion, power dynamics, and at its most extreme — torture. It is bereft of the “blurriness” that Trammell believes is inherent both to Black culture and a more useful definition of play.

Rascal spoke with Trammell about Repairing Play’s significance to tabletop culture, how it might be applied to very recent events around itch.io and effective censorship, and why we must seek both the joy and pain within play.

This interview has been slightly edited for clarity.

Rowan Zeoli: Did you find difficulty once you got into game studies? Were there challenges in breaking into it in this way once you got there?

Aaron Trammell: Game studies was having a moment when I got into it. And I don't want to say the moment was so big that they were just giving out jobs, but relative to some other academic fields like English or history, the jobs were there. They existed, and they were in the market. The thing that wasn't having a moment in game studies was tabletop games. You'd go to a game studies conference in 2012, and people may have heard of Dungeons & Dragons or referred to it in an essay, but nobody was doing any kind of research into tabletop games, Dungeons & Dragons or Magic: the Gathering. It seemed like an opportunity to study.

I remember one of my very first projects in grad school was this ethnography where I was going to Magic: the Gathering shops and trying to understand how the digital experience of playing Magic Online — not Magic Arena, Magic Online — differed from the experience of playing Magic at tournaments in real life. It was an exciting thing. It was really great to talk to people in real life about the games they were playing. My partner at the time played a lot of Magic, and she actually preferred to play it online because no one knew that she was gendered female. She wasn't getting harassed in stores, discriminated against, or mansplained (this is how this rule works, little lady). It wound up being a really interesting thing that had a lot of ramifications for the people I cared about.

Zeoli: The book that I really want to talk about is Repairing Play: A Black Phenomenology. How did that specific avenue of examining games come to be?

Trammell: Repairing Play is a great story. It started as a philosophical concept that wasn't really tied to an idea about race in America, or BIPOC people globally. That, I think, was actually the thing that tied the ideas together because it was pretty incomprehensible to people when I did it first. There's a fun story: I'd go out to conferences where we academics share a work with each other, and I'd try to talk about the book. I'd go into the audience, touch someone and say, tag, you're it. Sometimes, a little bit of tag would break out. Sometimes, people would look at me awkwardly, and it'd be very uncomfortable. This was, of course, kind of the point. It was a little bit of performance I was doing, which is that play isn't always fun, play isn't always consensual, and sometimes when someone's playing, you're being played with. But because I didn't have more of a contextual avenue, people in this moment of game studies thought I was saying, hey, golly gee whiz, isn't it fun to play with people, and that you're sometimes a part of someone else's fun?

I took this thought experiment to conferences and confused a lot of people with it. Play, at its most basic is not a consensual, voluntary, person-to-person thing. It can be consensual, but I don't think it's voluntary. When somebody is interacting in a playful way — and that is nebulous — with an object, it doesn't have to be happy. That can be bullying, right? There's different ways that this thing we call play, which is kind of a non-verbal, intuitive communication that we creatures do — because I include my cats in this kind of thinking about play. I think it's something that we do to each other. I think that somebody is always playing with somebody else.

This makes a lot of sense when you think about computer games, when you think about playing music, or when you think about how play works grammatically. When we talk about play as this leisurely activity, we want it to be voluntary, and we want it to be consensual. Because fuck, who doesn't want to have a good time when they're playing? But the part of the story that got grafted in years later, which happened after the George Floyd murder, was I started thinking more critically about race, especially as somebody who is Black. I started thinking more critically about it. I started realizing that a lot of games, especially Black games or BIPOC games, aren't always happy stories. That's because a lot of BIPOC creators — and you can see this in some queer games as well, so I'd say minoritized creators more broadly these days — are familiar with what it means to be played with and are familiar with what it means to have to tell our stories through the medium of games themselves, and through play itself, which I think can be a very profound artistic tool.

"The people who wield power and influence create a pageant of sorts to fool us — the masses, the people — into thinking that we are outnumbered."

Zeoli: In the book, you use “repairing play” as both a noun and a verb. What is the intention behind that?

Trammell: That's because I'm sloppy. I'm being glib when I say that. There was a turn in philosophy in the late 20th century towards something called analytic philosophy, which seeks to sort out the affairs of our life in a very precise and logical way. Analytic philosophy wants to create situations where we understand the consequences and affordances of every decision and how it might fall — good, bad, or ugly. This is in contrast to another movement that begins in Europe called continental philosophy, which is what we generally call theory. It's the sort of tradition that thinkers like Marx, Foucault, and Judith Butler broadly come from.