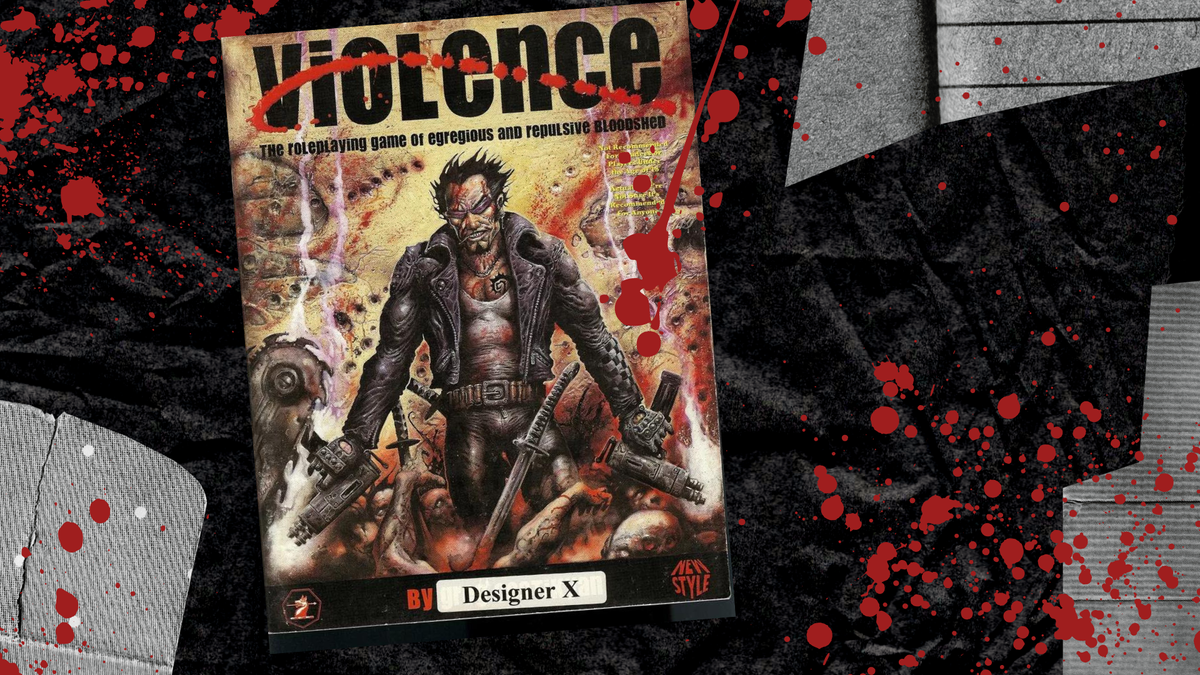

Violence might be 25 years old but it’ll still kick your ass

“The Roleplaying Game of Egregious and Repulsive Bloodshed” still contains relevant critiques of contemporary game design.

If you’ve never heard of Violence: The Roleplaying Game of Egregious and Repulsive Bloodshed, maybe it’s for the best. Set in a contemporary city–Boston and New York are recommended in the text—players are directly tasked with enacting the same kinds of violence in the present-day that they are asked to do in other games… like Dungeons & Dragons. It’s no longer a dungeon crawl, but a suburb-crawl, as player-characters—called Scum—break into houses, run from Pigs, and seek out the vulnerable to exploit. It is a book written in excessively bad taste, but it is also a book that directly examines the underpinnings of combat-as-roleplay and asks why we have so firmly lashed our imaginations to games that expect us to receive vicarious thrill from enacting harm, especially as we give ourselves good reasons within the narrative.

Published in 1999, Violence is an unapologetic middle finger to anyone attempting to read it. It’s aggressive–the audience is dismissed, degraded, and insulted on every page. It’s got a disaffected anger that absolutely rips off of it, a disdain so heated that it sears the edges of your game table. With Violence, the eponymous writer, Designer X, has carved out a bloody hole where roleplaying should be and instead inserted a blackened, moldy heart. At its core, Violence is a darkly comic, over-the-top satire of tabletop roleplaying games that puts the cruelty inherent in the design of D&D—and many other TTRPGs—underneath the mordant gaze of someone who’s seen all this shit before. It’s also one of the most incredible pieces of games writing out there.

Violence was written as a direct response to the author’s frequent experiences at the gaming table where a lot of “main character” types attempt to find the best way to enter into a space and do the most violence. Most tabletop games, no matter how you dress it up or what sort of backstory you add to your character, rely on mechanics of harm. After all, it’s one of the easiest ways to incentivize player movement in roleplaying games. If you have rules for combat, for harm, for violence, surely… violence is intended, in some way or another. There is no way to interpret design, if not an expression of intended use. “Genocide,” said Greg Costikyan—Designer X himself—on a call with Rascal, “is a great way to generate XP.”