Hack the orcs, loot the tomb, and take the land

Reflections on settler colonialism, Indigeneity, and otherwise possibilities in "Dungeons & Dragons."

In the United States, the Indian is the original enemy combatant who cannot be grieved.

—Jodi Byrd (Chickasaw Nation), The Transit of Empire (2011) 1

I grew up in a world of ruins, both literal and imagined. My mom’s hometown was Victor, Colorado, once a thriving Gold Rush city of over ten thousand reduced to around three hundred when I was a child. Everywhere around me were the picturesque remnants of nineteenth-century mining headframes, ore processing mills, fraternal-order temples, mercantile shops, and churches of crumbling brick, rough-hewn stone, and rusting iron, the askew residue of stolid industrial pragmatism and flamboyant nouveau riche fantasy. There were countless half-hidden old shacks, long-abandoned mines, and bleached tailings piles to be discovered throughout the arid pine- and aspen-covered mountains, a landscape seemingly forgotten and untouched by the modern world, discovered only by those willing to explore beyond the bounds of the past-haunted town we called home.

And then there were the “Indian relics” that occasionally surfaced, the arrowheads and spearpoints and the story of an unearthed Native burial site on the southern slopes of the mountain where my hometown sprawled, most of its buildings empty of all but dusty detritus and memory.2 In the account that my mom learned in her short stint as a tour bus driver for a local mine, early white “pioneers” in the area discovered a Native woman’s remains interred in a sealed grave, either somewhere on the slopes of the mountain or in a nearby gully. In that account, the body was looted and put on display in one of the nearby mining camps, but what happened afterward isn’t known. I don’t know if there’s any truth to the story, or if it was invented to explain the mountain’s racist toponym, but there’s a long and ugly settler history of grave robbing and exhibiting Native bodies—living and dead alike—so the story certainly has the ring of truth.3 Either way, the unmistakable message growing up in that place was that the Native presence in the region was fully in the past, and whatever ruins and fragments remained were little more than mildly interesting historical curiosities undeserving of dignity or care.

Those were the literal and storied ruins, but the familial ones, too, loomed large in our consciousness. “Heinz 57” is how my mom referred to her background, a motley assortment of British and western European settlers, including Ashkenazi Jews. (Like so many white Americans, they also claimed Native heritage through a convoluted and implausible story that seems to have been a way of laying claim to Chickasaw land during the allotment period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.)4 We didn’t know much about the Fay, Small, or Schryver families, as emigration, economic peril, sexual abuse, and class shame had severed many of the pathways through which meaningful stories might have been shared across the generations of my maternal kin.

Through my father’s maternal line, I am a citizen of the Cherokee Nation in what is today northeast Oklahoma, but while our kinship, political, and heritage links to the Nation are deep and significant, Grandma Pearl died of tuberculosis when Dad was a teenager, and between his own profound grief and his father’s hostile relationship to Pearl’s family, Dad was largely distant from his Cherokee kin (although his long-estranged sister Alverta maintained strong ties to our Spears relatives throughout her life). He was phenotypically Native, with dark skin and black hair buzzed to an invariable flattop; he was rarely seen without a well-weathered hat and had a seemingly endless supply of flannel shirts. But he wasn’t culturally connected, and what he knew of our family heritage was fractured at best until I was old enough to help him start putting those pieces together.

Though I had siblings from Dad’s first marriage, in many ways when growing up it was just Mom, Dad, and me. We lived in something of a closed bubble among Gold Rush ruins, in lands that had been violently seized from the Utes, Cheyennes, and Arapahos in the nineteenth century, a place haunted with stories of gold-hungry white miners and dead Indians, entangled in, but largely unfamiliar with, the complicated legacies of our mixed family lines. I would be in my late teens before we would reconnect with Dad’s sister and start to reweave those ties and gingerly attend to those histories, to begin to understand our place in our families and in relation to the very much living Nation.

On both sides of my family there was a sense that we were connected to a once-great past, that we were the unstoried remnants—sometimes bedraggled, sometimes just stubbornly enduring—of greater people with a firmer sense of their place in history and in the world. In the absence of any stories that might have helped me make sense of who we were in relation to our tangled histories, or active engagement with the living people and traditions I’d come to think of entirely in the past tense, I looked elsewhere for a sense of belonging. And where better for a dreamy, mixed Cherokee bookworm than a storytelling game set among the treasure-strewn ruins of a world inhabited by the scrappy but watered-down descendants of nobler peoples and their now-fallen greatness?

The great story of Faerûn is, in many ways, that of the rise of humankind and the fading of the ancient empires of those who came before. Over thousands of years, humans have brought an end to the old ways. Elven cities lie in ruins, abandoned to human encroachment. Hills and dells once the homes and hunting grounds of goblins and giants are now dotted with human fields and pastures. Human pride and folly have brought untold disaster down on Faerûn more than once, and the ever-growing lands of humans encroach on the territories of older races both benign and fierce.

Can the old races survive the dominance of humankind?

—Ed Greenwood et al., Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting (2001)

My first clear memory of Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) is of two beat-up boxes. The first was the 1981 Basic Set, referred to by old-school D&D nerds as the “Magenta” edition for the purple tones of the subterranean lair featured in Erol Otus’s cartoonish cover art of a sorceress and spear-wielding fighter fending off a green dragon. The other was the iconic 1983 “Red Box” featuring artwork by Larry Elmore, with a fierce red dragon bearing down on a courageous, horn-helmed warrior whose sword is captured in midswing at the moment of attack.

I’m not sure how these boxes came into my possession, but I was about ten or twelve, so likely 1985 or a bit later, likely a summer flea market purchase with my dad. I was too young to really understand the game, especially without other close friends to play with, but its storytelling possibilities fascinated me. I was delighted to discover that one of my favorite Saturday morning cartoons was connected to these books and had more than a superficial relationship to J. R. R. Tolkien’s sprawling legendarium, which I’d only just started to explore through The Hobbit novel and the animated films of Rankin/Bass and Ralph Bakshi. Soon after I found other D&D paraphernalia, including Endless Quest books, action figures, pewter miniatures, and gaming supplements from TSR and other companies.

I was hooked. D&D had everything I liked: storytelling, fantasy, adventure, inhabiting other worlds and characters. And the foundational template for all these works was one with which I was already intimately familiar, even as a child: savagism versus civilization. The stories of fallen empires and rising powers, decline and progress, primitive tribespeople and cultured settlers, made a kind of twisted sense to me, even though, deep down, I feared that I already knew where my family and I sat in that binary, and it wasn’t where I wanted to be.

Even so, when I started to create my characters, it wasn’t the brash (white) warriors who appealed to me, or the dignified (white) princelings seeking to regain their thrones, or the noble (white) paladins charging down the dragons to rescue the swooning (white) maidens in distress. These weren’t characters who reflected where we lived or where we came from. I struggled with shame about my little mountain town, far from what I envisioned as the center of culture, art, and intellectual achievement, but I loved the place, too; and so, to manage the cognitive dissonance, I began imagining myself in worlds of magic and mystery where difference was valued, not despised, where the game’s explicit insistence on the dungeon master’s (DM’s) ultimate authority as storyteller made it possible to ignore the parts that wounded and enhance those that empowered, no matter what the canonical rule books might otherwise state. The DM was the ultimate creator of worlds through story, and that was something I understood at a visceral level.

These sideways and otherwise fantasy worlds I cobbled together from scraps of game supplements, novels, comic books, cartoons, and my own imagination were the ones I wanted to be in, not the one of my everyday existence. For all that my home life was deeply loving and supportive, I internalized other corrosive ideas from my peers, from our neighbors, from popular culture, and even from the ruptures and absences in our own family. I came to see myself and my family through more judgmental eyes: the faggy, back-country weirdo with the run-down house and the loving but rough-hewn, brown-skinned dad and mountain-bred mom.

But rather than imagine myself among the privileged, I doubled down on the outsiders. My imagination wasn’t so detached from reality that I easily envisioned being one of the cool, the privileged, the easy elite. Misfits were the only characters with whom I really related, but misfits with power and purpose, motley fey folk and half-elves and wise women and witches of inborn talent and trained skill, for whom courage and intelligence were more than a match for plain physical prowess. Though displaced and erased in most fantasy settings, they at least had a certainty and clarity that my own world seemed to lack.

It was the Basic Set’s “demi-humans” who appealed the most, in spite of being manifestly less powerful and having fewer ability options than humans: the elves, dwarves, and halflings whose character class was the same as their race. They were outsiders, associated with the land and the wild places of the world; even if they were inferior in skills compared to the human characters in the game, they felt far more recognizable to me than their more powerful human counterparts. For all that they drew on stereotypes, some of those stereotypes were ostensibly positive, the noble savage infinitely more appealing than its ignoble counterpart. These were the figures that spoke to me and my growing interest in fantasy role-playing. And that continued even as I moved to Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, where more scope existed for character advancement, if not much change in the foundational ethos of the game. (In chapter 17 of this collection, Aaron Trammell and Antero Garcia share their own reflections on these retrograde racial taxonomies and game mechanics as young mixed-race players. How many of us similarly found both empowerment and ensnarement alike in our first racialized engagements with D&D?)

It’s fair to say that I didn’t feel entirely human myself; among the vast majority of people who lived in Victor in the 1980s and ’90s, as in so many places throughout the United States then and now, full human status was determined by proximity to unsullied whiteness and Euro-Western culture. Whiteness determined both dignity in life and grievability in death, and even though my own features were lighter than my dad’s, and my own proximity to the myriad privileges of whiteness infinitely more secure, there was always a shadow of uncertainty, one compounded by the instabilities of heritage, class, income, education, and the growing awareness—my own and others’—of my nascent queerness. Social acceptability seemed tenuous at best, as the harder I tried to embody what my world deemed “normal”—white, straight, culturally sophisticated, well-spoken, and so on—the more that goal receded into an inevitably unachievable distance. Everything seemed to betray me: my parentage, my hometown, my education, my desires, my features, even the pitch of my voice. So if my humanity could only ever be a constant and embarrassing failure, my fantasy demi-humanity could at least be successfully realized. As a half-elf druid or a halfling ranger, I could be a celebrated hero, an honored compatriot, a desired lover; as myself, I could only ever stumble awkwardly toward belonging. Better to imagine the integrity of being an outsider in totality and not just in pieces and parts that were destined to betray me in spite of my best efforts to fit in.

Of course, humans and demi-humans weren’t the only beings in D&D: these worlds were full of monsters, too, the “savage peoples—goblins, orcs, ogres, and all their kin . . . [who] regularly burst forth from their strongholds to pillage and slaughter villages and towns unfortunate enough to be in their path.”5 From tribal goblinoids to dragons, beholders and bullywugs, even the degenerate civilizations of the fallen-from-grace dark elves, monsters were obstacles—not just to the adventurers, but to civilization itself. Thus their subjugation was not only an act of self-preservation but the highest possible good to defend civil society, history, family, and social order.

And this is where the savagism-versus-civilization binary really came in, for the function of monsters was—like that of all savages in this ideological structure—to die, and thereby give certainty of purpose to the civilized. One side in this binary is culturally complex, sophisticated, literate, and ambitious, and the other is brutish, superstitious, and little better than mindless beasts. Civilization depends on its opposite; without savagery for negative comparison, there is no civilization. Even when the savages are given complex emotions and cultures, they rarely escape the binary—noble savages from once-great cultures die just as readily as ignoble savages, but there is a sense of resigned if nostalgic sadness for the inevitable fall and fading of the former, while the latter are mown down like so much crabgrass. The Ignoble Savage is a menace, but the Noble Savage is a warning: it heralds what can happen when a civilization becomes complacent, soft, or degenerate. Together they are an object lesson for the rising powers: stay virile, stay robust, stay vigilant; otherwise, you degrade or you fade.

And the association of both the demi-humans and the monsters with Indigenous and colonized peoples was hardly coincidental. Indeed, it was baked into the earliest iterations of the game, as Eugene Marshall notes: “It’s hard to ignore the fact that, when he first created miniatures for the fantasy races, Gary Gygax chose Turk minis to depict orcs and repainted Native American figures for trolls and ogres.”6 Indigenous peoples were rendered monstrous and therefore killable, neither one worthy of mourning or compassion; the savage dies so that the civilized may flourish, no matter how bloody the cost.

But I didn’t relate to the righteous killers. I can’t remember even once playing a human character in D&D—all my characters were fully demi-humans or half-elves, and most were women or genderqueer. Only later did I realize that was because I related not to the masculinist human champions but to the goblins they killed without mercy, to the elves and dwarves they sent fading into history, to the seemingly weak halflings slipping through the shadows of lands they’d always called home. My imagination lay with those who inhabited the ruins, those who remained, furtive but defiant, the peoples far less cruel than the ones who persecuted them and called them monsters.

The Indian who was important to Americans setting out to make their new society was not the person but the type, not the tribesman but the savage, not the individual but the symbol. The American conscience was troubled about the death of the individual. But it could make sense of his death only when it understood it as the death of the symbol.

—Roy Harvey Pearce, Savagism and Civilization (1953)

In spite of the superficial polytheism and diverse deities influencing the various world orders, there’s also a kind of Christian triumphalism at play in D&D, with clerics and paladins in righteous crusade against the forces of darkness, with darkness versus light mapped readily onto the savage-versus-civilized underpinnings.7 (This might have reassured the Christian fundamentalists during my youth who insisted that the game was inherently satanic.) As befit its wargaming origins, D&D depended on such dualistic conflicts at all levels, in all interactions. The bold and righteous fight to survive and bring civilization to the wilderness, but the unrighteous—the savages, the heretics, the cultists—exist only to be killed. Indeed, beyond the cultural crusade of civilization, killing savages—religious as well as racial and cultural—has been, for most of D&D’s history, the main way for characters to advance in level, power, and skill. In the game, they are heroes and champions; in life, they would be sociopathic war criminals at best. But in colonial frameworks, Turks readily become orcs, Native Americans readily stand in for trolls, and if you accept the binary, there’s only one direction that story goes.

As I grew older and began to connect the dots between my family’s entangled histories and my love of fantasy, it became increasingly clear that, in the dualistic Christo-colonial cosmologies of D&D, my world and so much of my family could only ever be on the savage side of that system. The plundering of lost tombs lost its excitement when I began to learn how many treasure hunters had robbed Indigenous graves and burial sites, how many looters had destroyed important cultural sites, how many companies and individuals had wrested vital ceremonial places and objects away from our nations, how the lives and livelihoods of working-class people were so easily taken away by those with power and impunity. The destruction in the 1930s of the Craig Mound in Oklahoma—part of the Spiro Mounds site on the Choctaw Nation reservation—put all treasure-hunting adventure stories in a very new and unpleasant light, while an ugly repatriation controversy during my graduate school years also opened my eyes to the myriad harms such thefts enacted on living communities, even long after the initial robbery.8 A lifetime of watching multinational mining companies use up the land and the people and then abandon both when profits went down made it clear that the hierarchies of that binary had their class dimensions too.

No longer satisfied with pseudomedieval, pseudo-European worlds of prophesied monarchs returning to thrones they claimed by right of blood, I was far more interested in stories that spoke to lands, cultures, and contexts closer to home. And soon the Tolkienesque template of D&D began to chafe, as did the varied inheritors of Tolkien’s literary imaginings. (The other great influence on D&D’s world-building, Robert E. Howard, especially his Conan works, held no appeal for me whatsoever, as there was no beauty, no grace, no romance—just blood, brutality, butchery, and overt racism.) As much as I loved Middle-earth, it was still a world where lordship was borne in the blood, where inheriting country gentry were served faithfully by loving and dutiful servants, of the uncertain triumph of “Western civilization” over the dark and fallen peoples who stood against it. And while Tolkien’s orcs and their filmic, gaming, and media iterations have been shaped by and expanded on savagist anti-Black and anti-Asian stereotypes, they’re also informed by stereotypical ideas about Indigenous primitivism (as are his Drúedain, the reclusive Woses who aid the Rohirrim on their way to the Battle of the Pelennor Fields).

I still loved D&D, but everywhere I turned, the savage versus civilized binary flourished. The designers of every edition grappled with it in different ways, sometimes challenging it, sometimes burying it, but as Amanda Cote and Emily Saidel have demonstrated (see chap. 15 in this collection), the basic template has remained troublesome, making it extremely hard to shift these deeply rooted and widely held cultural biases. The Atruaghin Clans of Mystara recycled almost every problematic Hollywood and pulp western stereotype about Native peoples, in both the noble and ignoble savage modes; Dragonlance had its noble savage (but blond!) Plainsmen right out of Dances with Wolves, along with the execrable gully dwarves, a people depicted as so primitive, degenerate, filthy, and simpleminded that their more civilized dwarven kin actively sought their extermination; Forgotten Realms was explicitly based on the civilized-versus-savage binary and leaned in hard on racial essentialism in its sadistic black-skinned drow led by vicious matriarchs and their terrible spider goddess, firmly melding anti-Blackness with misogyny, a once-civilized people gone feral under the debased rule of women. Ravenloft had its pseudo-Roma Vistani, complete with the worst “gypsy” stereotypes of criminality and charlatanism. And where to begin with the tribal cannibals that were the Dark Sun halflings? With savagism versus civilization as the structuring logic, changes could only ever be superficial, and those supplements that extended too far outside the logic didn’t tend to do well. (For all that I objected to The Atruaghin Clans, I still think that the 1990 Mystara gazetteer The Shadow Elves, by Carl Sargent and Gary Thomas, offered a fascinating spin on the “dark elf” trope that was far more complex, more imaginative, and less burdened by racist stereotypes than the drow have ever been.)

Other fantasy game systems and imagined RPG worlds weren’t much better. Warhammer, GURPS, HârnMaster, Palladium, Shadow World—few systems seemed able to imagine beyond the underlying dualistic and extractivist logic that so deeply informed D&D, even when seemingly inclined to do so. So I started looking elsewhere. The first few story lines of Wendy and Richard Pini’s Elfquest series of fantasy comic books shook me, for here was a world that, while not without its essentialist limitations, nevertheless showed cultures not simply in conflict but in quite complicated relationship. Some of the elves were brown-skinned desert dwellers; others were light-skinned forest folk with deep other-than-human kin bonds; all were complex, and all had sophisticated cultures and social systems. Sex and desire were natural parts of the characters’ lives; there were triads, queer relationships, and even a lovingly rendered group love-in in one issue.

Octavia Butler’s Wild Seed and other Patternist volumes in the “Seed to Harvest” series were all about people of color finding a space of their own in a world that too often subjected them and their desires to bodily indignities; Butler was the first fantasist of color whose work I ever read, and she had a profound impact on my own desire to write Indigenous fantasy novels of my own, stories that took Indigenous cosmologies and relations and power dynamics seriously, and where identity was rooted in land, language, and kinship that included other-than-human beings and subjectivities. Dignity, love, passion, courage, complexity—these were the motivating forces of these otherwise worlds, and they opened up vistas I’d longed for but couldn’t quite see in my solitary imaginings in the mountains.

In these new fantastical places, the “civilization” and “savagery” binary didn’t dominate or even operate; the main characters were driven by purpose and principle, not by unearned power, and struggled with the very real effects of colonization, enslavement, bigotry, and fear, not simply reacted passively or without reflection against an externalized threat. It’s no surprise to me now that most of these writers were feminists who were, to varying degrees, politically and intellectually sensitized to the struggles of oppressed peoples, with the linguist Suzette Haden Elgin and the visionary Ursula K. Le Guin joining Butler among my literary favorites. And there have been so many justice-oriented feminist and queer and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) writers and artists since, each imagining other worlds beyond the extractive limitations of settler colonialism and its impossibly narrow dualisms.

But I didn’t let go of D&D, not completely; I remain a player and a DM, in homebrew worlds where the savagism versus civilization binary is actively contested, where diverse genders and queerness are normalized but rape and sexual objectification aren’t, where restoration of lands, languages, and kinship are far more important than achieving wealth or glory. In these imagined worlds, grave robbers are villains, not heroes; today’s peoples aren’t the pathetic remnants of once-great cultures but complicated and enduring people doing their best to thrive even in difficult circumstances. My fantasy series The Way of Thorn and Thunder directly explores issues around Indigenous dispossession and restoration in a secondary-world fantasy setting that started as one of my homebrew worlds, and three of the main characters were my own player characters (PCs): Tarsa and Tobhi were my first PCs (though fortunately very different in the novels than when I first conceived of them), and Denarra was my unashamedly queer alter ego from a multiyear gaming group during my undergraduate years. These characters embodied and expressed parts of me I didn’t understand at the time. We’ve been on a lifelong adventure together.

Though decidedly not the only influence or source of inspiration in my life, and though not without its myriad problems, D&D was one way I found a partial if imperfect language for naming my world, its limits, and its possibilities in all its contradictions, complexities, and diversity. The game’s own limitations—and the alternate visions of BIPOC, queer, and allied fantasists—helped me see myself and my family as not simply broken and ruined but meaningful and complicated in our own ways, and to understand the very real kinship and cultural fractures in our histories not as an inevitable consequence of our essential natures but as the results of historical forces, violent structures and institutions, and individuals who made choices—some of which we were actively complicit in, some of which we resisted, some of which we embraced, and some of which were forced on us.

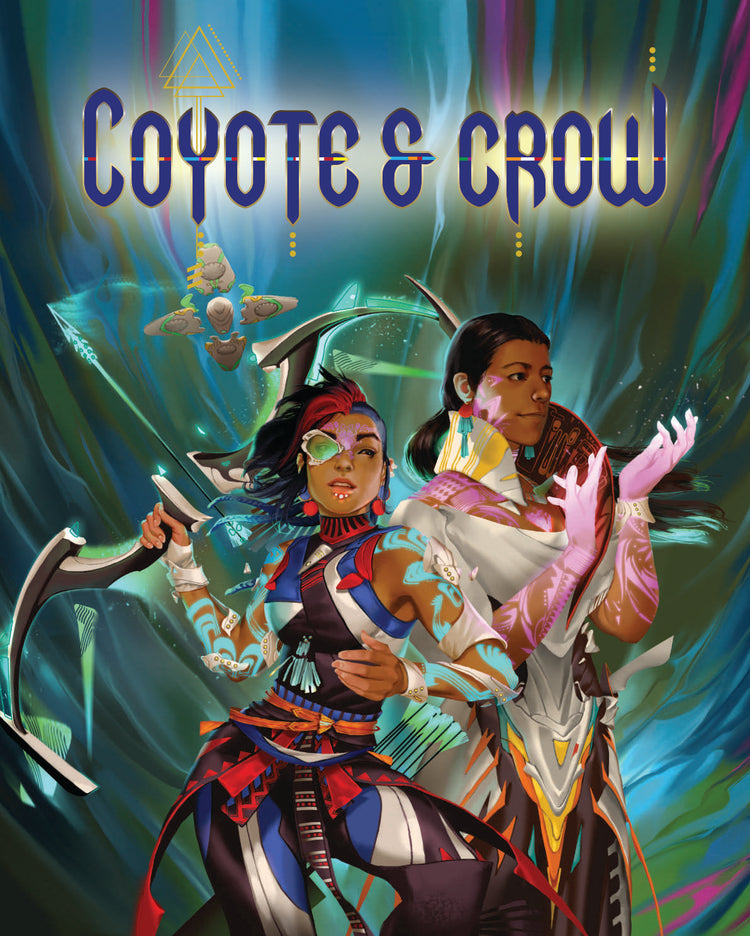

The world of tabletop role-playing is very different now from when I was coming of age in the game: no more accepting the most overbroad stereotypes simply because they at least had a slim hint of Indigenous resonance, the thin leavings on bones tossed from an imaginative banquet others could enjoy with more gusto. I’m delighted that there are Indigenous gamers and game designers working hard to present otherwise possibilities in their own gaming worlds and systems (with Coyote and Crow being an important step forward), alongside Black game designers and visionaries from other communities, cultures, and contexts. BIPOC, queer, and otherwise marginalized players haven’t entirely given up on D&D itself, either; a lot of us still work to make it our own, with our own stories and our own cosmologies, and have brought this to a broader public, as the NDND All-Native D&D gamers have done on their YouTube adventures and as seen on the Indigitek Blak All-Stars game on Twitch. While not entirely escaping some of the problematic underlying structures of D&D, the Arcanist Press Ancestry and Culture fifth edition gaming supplements are helpful reimaginings of identity outside the static essentialisms of race.

Even Wizards of the Coast (WotC) is responding in official D&D content— part of a larger company-wide move to address sexism, homophobia, and racism in published content—although not entirely successfully, with the controversy around Graeme Barber’s experience with content he wrote for Candlekeep Mysteries (2021) a case in point. Barber’s original material intentionally complicated the frog-like Grippli people, taking them from past representations as a simplistic and “primitive” bipedal frog folk to a more nuanced and complex society. According to Barber, the WotC editorial team revised his material toward more retrograde, primitivist directions before the book was released, which he discovered only after its publication.9 A disappointing retrenchment into savagist stereotypes, but new designers and new projects in development give me hope that these reversals will be the exception rather than the rule.

Indigenous fantasists and wonder-workers are flourishing globally, especially in the last decade, finding appreciative audiences within and beyond our nations: Daniel H. Wilson, Andrea Rogers, Richard Van Camp, Chelsea Vowel, Darcie Little Badger, Stephen Graham Jones, Sara General, Gina Cole, Tihema Baker, Ambelin Kwaymullina—just a few of the visionaries creating Indigenous worlds beyond the colonial now. Indigenous gamers are using social media to find one another, and we’re playing and learning with and celebrating one another all over the world. Our writers and artists and gamers and DMs are creating richly imagined and complex Indigenous futures where Indigenous lives, lands, and relations continue to be strong, unbroken, and undeterred, collectively enriching our imaginative horizons in ways that were far outside my lonely, limited scope when I was a disconnected mixed Cherokee kid in that little Colorado mountain town flipping through my Basic Set.

The solitary worlds I made up in my head were one way I could imagine my way around the ruinous settler presumptions of mainstream society, presumptions I had internalized in so many ways but still struggled against. If I’m honest, I still grapple with them even now. I can’t know how much more my imagination might have expanded, and my journey into accepting so many parts of myself been so much easier, had I been part of an online community like NDND, read wondrous fantasy novels by Indigenous writers, or even had just one other Indigenous gamer to play with in my hometown. The internet has made these connections possible in ways that were unimaginable when I was an awkward and lonely kid in a world that just didn’t seem to have a place for people like me and my family except among the ruinous reminders of a distant past.

For all its problems, I’m still glad I’ve had D&D in my life. I’m glad that so many people from so many backgrounds and identities have found something worthy and affirming in this strange, empowering, problematic, and complicated game. I’m also glad that people are challenging the game, pushing back against its calcified traditions, refusing its baked-in bigotries. I’m certainly not one of those longtime gamers who bemoans the growing popularity and social justice concerns that now inform so much of the game and the way it’s played—I wholeheartedly celebrate these changes. My own experience would have been far less vexed, the struggle and uncertainty far less onerous, had these been part of our conversations back then.

But even more than all that, I’m immensely grateful that D&D has inspired, in both its best and its worst, new ways of imagining vibrant Indigenous futures far beyond the haunted ruins of the settler colonial imaginary. Had he known about them back then, I think that queer Cherokee kid rolling his d20 and dreaming of wondrous vistas within and beyond his little mountain town might have taken great comfort in these otherwise possibilities, too.

Notes

1 - Jodi Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), xviii.

2 - For over a century, the mountain and a nearby ravine shared the name of a degrading and abusive term used against Indigenous women. In 2022 the US Department of the Interior removed these violent place names, replacing them with the far more evocative Evening Star Mountain and Maize Gulch. See US Department of the Interior, “Interior Department Completes Removal of ‘Sq*’ from Federal Use,” September 8, 2022.

3 - The terrible story of Julia Pastrana, an Indigenous woman from Mexico who was exhibited as a sideshow “freak” by her white husband in the mid-1800s and who was, along with their infant son, stuffed and displayed after dying from complications of childbirth, is one of the most ghoulish cases, but by no means anomalous. See Warren Cariou, “The Exhibited Body: The Nineteenth-Century Human Zoo,” Victorian Review 42, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 25–29; Linda Frost, Never One Nation: Freaks, Savages, and Whiteness in U.S. Popular Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005); Pascal Blanchard et al., eds., Human Zoos: Science and Spectacle in the Age of Colonial Empires (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008).

4 - See Daniel Heath Justice, “Narrated Nationhood and Imagined Belonging: Fanciful Family Stories and Kinship Legacies of Allotment,” in Allotment Stories: Indigenous Land Relations under Settler Siege, ed. Daniel Heath Justice and Jean M. O’Brien (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022).

5 - Ed Greenwood, Sean K. Reynolds, Skip Williams, and Rob Heinsoo, Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting (Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast, 2001).

6 - Gwendolyn Marshall, Ancestry and Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5E (Arcanist Press, 2020), 5.

7 - Roy Harvey Pearce, Savagism and Civilization: A Study of the Indian and the American Mind (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1953), 73.

8 - See David La Vere, Looting Spiro Mounds: An American King Tut’s Tomb (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007); Ellie Churchill, “Bones Unearthed and Respect Burned,” Nebraska U: A Collaborative History, n.d., accessed February 25, 2022.

9 - Chase Carter, “An Author Is Questioning Wizards of the Coast’s ‘Problematic’ Changes to His Adventure in the Newest D&D 5E Sourcebook,” Dicebreaker, March 24, 2021, accessed February 25, 2022.